Wit to Plot this Drift: 20 Summers of Driftwood

I could fill ten thousand words speaking to you about the youthful pursuits of nights spent loving, laughing, drinking, singing, dancing — experiencing everything in a College-like haze of friends and laughter, each tale as ethereal and outstanding as the last. Driftwood moments fill every one of my “formative” memories. Where most people in their ‘remember when’ moments tell College stories, I tell Driftwood stories.

Dan Gallo (Founding Company Member, Actor (4 seasons), Technical Director, Production Manager, Lighting Designer and/or Sound Designer (12 seasons).

Wit to Plot This Drift: 20 Summers of Driftwood Theatre in Ontario

by Dr. Toby Malone, dramaturg.

The survival of a small theatre company is cause for celebration. 2014 marks the twentieth anniversary for the Driftwood Theatre Group, Ontario’s longest-running touring Shakespeare company. Founded as a tiny passion project for a collection of Queen’s University students in 1994, Driftwood has become, through twenty seasons of touring, an Ontario institution. In that time, Driftwood has out-lasted dozens of similarly-mandated companies, and has led a new renaissance of fledgling companies built on Driftwood’s success. The mercurial nature of the ‘summer Shakespeare’ industry is reason enough to celebrate Driftwood’s survival after an industry-wide death knell proclaimed after the shuttering of ShakespeareWorks (Toronto), Resurgence Theatre (Newmarket), Canopy Theatre (Toronto), [the original] Shakespeare in the Rough (Toronto), and Festival of Classics (Oakville), a series of closings which Driftwood weathered with aplomb.

The very fact that Driftwood has managed to thrive and grow over the past twenty years is cause enough for celebration. The economic plights that have impacted the artistic community during that time, including the SARS outbreak which sucked out-of-town money from Toronto, and a global financial crisis which, which mild in Canada, led to austerity measures in programming and a general decline in audience numbers. Grants became harder to come by, and well-established companies threw in the towel left and right. But not Driftwood. If anything, Driftwood has grown over the last decade to include youth training programmes, ambitious forays into new areas of Ontario, the hugely popular Trafalgar 24 playwriting contest, and its run-on play development of new works. To mark the twentieth anniversary of the Driftwood Theatre Group, and in anticipation of this summer’s coming production of The Tempest, I have spoken to members of past companies, audiences, and boards to evaluate just what it is that makes this scrappy little company what it is today.

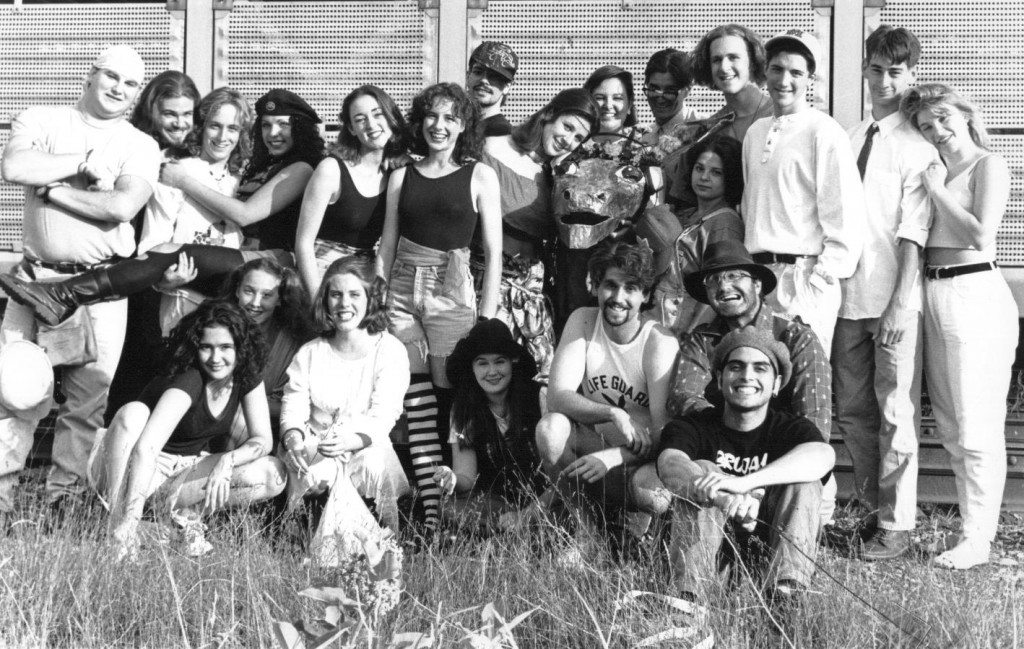

The inaugural Driftwood Company, including current company members Steven Burley (back row, second from left), D. Jeremy Smith (back row, third from left) and Dan Gallo (back row, fourth from right).

A Brief History

Driftwood is my theatrical home, a place where I have stretched my acting muscles and where I have been allowed to find my voice as a writer. Through Trafalgar 24, [Driftwood has] been instrumental in guiding me as an artist, and in my late 40’s has given me a whole new career.

Steven Gallagher (Actor, King Lear, The Comedy of Errors, 2010, Playwright, Trafalgar 24 2010-11; Beyond the Castle: Memorial 2012; Director, Trafalgar 24 2012)

The company’s very name is evocative: a piece of driftwood is smooth, it has been shaped by its environment. It travels where it will, even into places where it is not naturally occurring. For a theatre company, ‘drift’ is a touring transience on gentle leading currents; ‘wood’ evokes age-old images of ‘treading the boards’ and ‘two planks and a passion’. In nature, driftwood is created by happenstance: a branch or beam is pitched into an unfamiliar environment, and, through the rough-and-tumble of time and experience, is shaped into something new, and beautiful. Without needlessly labouring the analogy, the Driftwood Theatre Group is perfectly named: a company born from a whim – almost accidentally – shaped and developed by time and experience to emerge as something unique, and prized. The ‘wit to plot this drift’ of this article’s title is more than a nod to The Two Gentlemen of Verona; it is acknowledgement of those many ‘wits’ who have worked to help Driftwood become what it is today. While founding artistic director and general manager D. Jeremy Smith is the backbone and the lifeblood of Driftwood, it is crucially important to remember that this enterprise is not called the Driftwood Theatre Company – it is the Driftwood Theatre Group, and it is the contribution of many hundreds of artists, volunteers, and audience members which has helped ‘plot’ the ‘drift’ of the last two decades.

Driftwood began as an idea in a 1994 Theatre History classroom at Queen’s University in Kingston. Jeremy Smith, a third-year drama student, daydreamed about how he might one day play the role of Puck in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Jeremy believed that the best way to get work is to make work, and inspired by outdoor theatre enterprises like Montreal’s Repercussion Theatre and Sarah Stanley’s Die In Debt, decided to make it happen himself. To get the ball rolling, he approached his father, the indomitable and beloved Howard Smith (a fixture in the Driftwood front of house since day one), to discuss a potential production in his home region of Durham, Ontario. A company name was hastily chosen to reflect a road mentality – for the group toured, albeit briefly and locally, from that first season – and eventually a logo was designed, based on an actual piece of driftwood displayed in Howard and Barbara Smith’s dining room. That first logo, designed by (now Eisner Award-winning) artist Ramon Perez, reflected the company’s mandate: a piece of driftwood, partly enclosed by a box, but emergent at either end, breaking its confines. That first, dreamed-of production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was cast from a collection of local actors and friends, with a $2000 budget donated by local businesses. Jeremy’s innovation was locally admired, yet his subject choice was questioned: “who would come and see Shakespeare out here?” Nonetheless, Driftwood was founded – initially a one-shot deal – and many of those first-season skeptics are still staunch Driftwood supporters, a generation later.

There was no outdoor Shakespeare in Durham, and little theatre beyond community groups, which offered a niche. The company banked on warm summer weather and an invitation to enjoy a picnic on the grass, for Jeremy was determined that this would be a performance for everybody. That meant no fences, no tent, no ticket-takers, and no mandated fee, all of which diminished profits but guaranteed Pay-What-You-Can integrity. Driftwood veterans tell stories of audience members accidentally happening by while out walking their dog or running an errand; each serendipitous visitor is approached by a Driftwood volunteer and told about the event. They are invited to stay and donate if they wish; if not, then they have been welcome for that short time. As Jeremy stated in a lengthy interview I conducted (and will quote from throughout), “theatre has no worth unless all people have access to it.”

The first tour started in Lakeview Park, Oshawa (which will host 20th anniversary season opening night), and also included stops in Whitby, Bowmanville, and Port Perry. The permission process was beautifully naïve in those early days, as the company simply approached the city to ask permission to set up shop for a few nights, for free. Eventually this grew: in the second season the tour expanded to Ajax, Pickering, and Peterborough (a venue where Jeremy remembers Driftwood’s first negative review: apparently this Romeo and Juliet was too ‘punk rock’ for the Kawarthas). 1998 saw an Ontario Gaming Commission grant which extended the tour east to Kingston: a defining moment for the idea of this tour’s staying power. The following year, the company received its first grant from the Ontario Trillium Foundation, which meant actors could be paid for the first time. By 2001, the tour had grown to include the now-legendary ‘cottage week,’ in which the company descends on the Smith family cottage in Prince Edward County for days of cottage fun while playing satellite communities at night. The vast majority of interviewees for this article dwelled on the cottage week, an element which helps keep Driftwood so unique. Stratford actor Bethany Jillard, who started her career at Driftwood as a teenager, characterised the tour as “quality professional theatre and … summer camp all rolled into one!” Jeremy once resisted this ‘summer camp’ designation, but he embraces it now, in the knowledge that it speaks to a joyful release offered in relaxing on tour with other artists. Unlike many tours, Driftwood is primarily ‘run-out’ focused, which means that with the exception of portions at the extreme ends of the tour’s geography, actors commute to and from shows in the ‘Bard’s Bus’, and sleep in their own beds for much of the time. This is, of course, after the set has been stowed: another (somewhat less beloved) Driftwood tradition is that everyone contributes to packing sets, costumes, and props, a chore which, under the stage management team’s watchful eye, becomes gradually more fluid as the tour wears on.

Locations, communities, and regions have changed over the years, but the modern Driftwood tour takes in twenty-five communities over ten regions, West to London; North to Bobcaygeon; and East to Westport. In the company’s early days, partnerships with communities were established through cold-calls and persuasion: today, communities contact Driftwood directly, often in areas with little regular theatre exposure. Some community partnerships have lapsed due to scheduling or interest, but the fundamental tour structure remains. Other changes have made things easier: since 2010, an Ontario Arts Council grant has helped cover operating costs, while concerted fundraising efforts saw the purchase of a beautiful new (and tastefully branded) tour bus. Jeremy has acknowledged from day one that he was not going to make money from Driftwood: that wasn’t the point. The point was always to create work with intrinsic value, with the understanding that the company would always be on the precipice. The upside of the precipice, however, is the fact that Driftwood has never had the luxury of coasting, and this shows in the quality of its work.

From a stagecraft perspective, Driftwood transitioned from a mobile proscenium stage in 2007 to its now-signature theatre in the round. The small, elevated deck (and accompanying upgraded lighting rig) allows for minor artistic flourishes but the set-up ultimately calls on the audience’s imagination. With spectators on all sides, actors must often flex strange performance muscles, and rehearsals are a lot about body orientation and remembering what aisle to exit. The centralised stage heightened the storytelling opportunities, and simplified the need for design flourishes. Ultimately, for Driftwood, the ‘bells and whistles’ are not what theatre is about: bells and whistles don’t tell a story, people do. Driftwood eschews the temptation to wrap the core of the product in packaging to make it more appealing, focusing instead on the heart at the centre of the piece. In Jeremy’s words, “it’s just window dressing unless you have a story at the centre.”

The Man with the Vision

“I am always delighted to see what D. Jeremy Smith has in store (for me he is the real star of Driftwood) with the way he directs and casts his productions. I always look at the play in a different way thanks to him.”

Lynn Slotkin (critic, www.theslotkinletter.ca, Juror, Trafalgar 24)

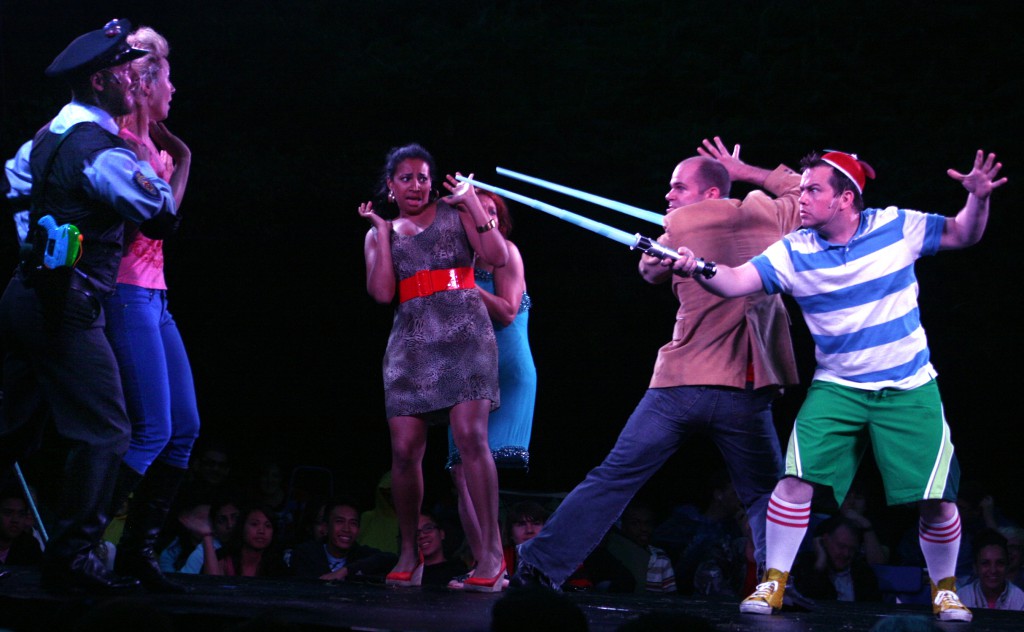

Jeremy Smith is an inspiring man. The first thing you’ll notice about him is his diminutive size, but this should not be equated to the energy that he has harnessed. The passion that drives Jeremy in all elements of his life – and he has many beyond Driftwood, including his art, his Star Wars fixation, and his beautiful family – has been transferred to Driftwood in spades. Some of the more eclectic events that Driftwood holds, like its annual progressive Euchre tournament, are done so precisely because those are things that bring him joy and he hopes to transfer that on. Despite the fact that Jeremy works almost exclusively on passion projects, it should not be assumed that he is any kind of pushover. When Jeremy has a vision in mind, it is very difficult to shake it, for better or worse. As his dramaturg for the last eight years, I can strongly attest to the staunchness of Jeremy’s determination with his artistic ideas. Above all things, Jeremy values loyalty and industry, exemplified in the fact that he tours with every production, and sees virtually every performance, something not expected of most directors. This, of course, can have built-in surprises, like in the 2006 season when Chris Darroch broke his foot in preparation for the three-hander Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged). Chris, as fate would have it, was playing the role which included all of the frock parts, in a high-energy piece developed over years by the virtuosos at the Reduced Shakespeare Company. Yet without any other choice, Jeremy stepped into Chris’s skirt, learned the role in one day, and performed a dozen shows until Chris could walk well enough to return. In 2014, as fate would have it, Peter Nicol’s unexpected relocation out west meant Jeremy had to slot in to one of the Complete Works’s other roles for a fundraiser with very little notice. There was no question either time of cancelling the show with the late cast change: a determination and vision saw it through for the company’s sake. That’s Jeremy.

If you’re ever interested in seeing Jeremy sweat, ask him to tell you his favourite Driftwood production. He has been involved in every single one, as director in all except the first couple of seasons when Alicja Francis took the helm and Jeremy acted. Each production has its own place of importance in Jeremy’s heart: he loved the first Dream because it started it all. He loved the artistic success of The Odyssey (2013) but wished more people had seen it. He loved The Complete Works partly for the stories described above but also because of its popular success. There were a few shows he felt he would like to have another try at, another opportunity to adjust some things that didn’t quite meet his vision. The show that Jeremy and several other respondents picked out as special was Much Ado About Nothing (2007), a production which saw the company’s greatest exposure in the national media. In response to this Much Ado, Richard Ouzounian of the Toronto Star said Driftwood “could teach most of this province’s summer Shakespearean theatres (yes, even that one in Stratford) a thing or two about simplicity and clarity.” We’ll take it.

Ultimately, though, Jeremy’s favourite show is “the one I’m working on next.” This very fact says a great deal about Jeremy: he is not doggedly attempting to tick off all of the plays in the canon (he feels certain that he won’t get to them all, at least on the Driftwood tour), but he retains an inherent curiosity about what can be exposed in these plays. Successes or no, each production is an enquiry into the company’s mandated larger question on humanism and is the life Jeremy lives. He’s said he’ll keep making Driftwood shows “until I get it right”, which isn’t to say he’s got it ‘wrong’ so far: it’s more that his perfectionism means he can’t see an end in sight, although the recent addition of ‘father’ to his resume has made touring just that much more challenging on a personal level.

With that said, it is hard to see Jeremy Smith walking away: what appeals to him most is the company of artists on the road as they explore a collective question, and the journey they take to get there. One of the highlights at the close of each season is a caricature that Jeremy personally draws (as a gifted graphic artist) to summarise the season as a whole. Each cast and crewmember is included: nearly all are portrayed in some group activity but are immediately recognisable by a perfectly-captured quirk they displayed over the summer. Some summers it rains a lot. Some summers the bus breaks down. In some summers a running joke dominates. Each element makes it into the caricature, which is an extraordinary, beloved perk in an industry too often cynical, impersonal, and prone to wearing artists down. It is rare for an cast or crew member to not react with joy and wonder at the encapsulation of a summer’s work in a single sheet, beautifully coloured and lovingly rendered.

Driftwood, Community, and Accessibility

I love Driftwood. I love Jeremy, I love the people he brings together each summer, I love his family, I love acting in his productions, and I love touring to small towns all over Ontario, where people seem to be more and more excited to see us each year, bringing their kids, babies, neighbours and dogs to see us.

Madeleine Donohue (Actor, A Midsummer Night’s Dream (2004), Twelfth Night (2010), Macbeth (2011), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (2012), The Tempest (2014), Trafalgar 24 (2005-07); Playwright, Trafalgar 24 (2013))

The intimate relationship between audience and artists is unique to Driftwood. To have the audience so close and feel them right in front, behind, and beside you, makes the playing so much more rewarding. We get to meet all these people too. After the show and before, we get to hear their stories and connect with these communities in a more special way than most theatre we do in Toronto or elsewhere.

Andy Pogson (Actor, Macbeth (2011), The Odyssey (2013), Trafalgar 24 2010-13)

Driftwood means ‘theatre for you’ in my perception. We treat rural communities as they want to be treated. We recognize their importance in the fabric of Ontario. To them, we offer a retreat from the everyday, and linkage to a romanticised past through the art of the play.

Brian Lenahan (Board Member, 2014-)

Theatre historian Stephen Heatley has suggested that the success of Canadian outdoor productions of Shakespeare relies upon “plays being adapted to fit a Canadian sensibility by a Canadian theatre aesthetic,” developed by artists who have “grown up theatrically with the Canadian voice at the forefront of [their] consciousness,” which results in a Shakespeare which “no longer feels foreign” (63). This is limiting: I prefer to suggest accessibility comes from an awareness of both a regional voice and an audience’s interests, which stretch far beyond simply an aesthetically-informed sensibility. It’s ludicrous to suggest that Canadian summer Shakespeare audiences respond to peculiarly ‘Canadian’ designs (hockey jerseys? Inuksuit? Snow shoes? McKenzie Brothers accents?) – this is reductive. Driftwood’s success has lain, time and again, in the stories that it has told and the accessible approach to those texts.

Over the last few years, Driftwood has adopted the slogan “Simply Classic,” which feels just right, so long as there is no suggestion that with simplicity comes a lack of intelligence. Shakespeare wrote for all audiences, not just elites, so companies who treat the works as something applicable only to a single set run the risk of ignoring a huge portion of audiences. With the same token, to assume that the best way to communicate with non-theatre goers is to play dumbed-down, ‘translated’ Shakespeare is a terrible insult to the intelligence, and only serves to alienate at the other end of the spectrum. Jeremy notes that “for all our society’s perceived reluctance to experience Shakespeare, [the works are] incredibly popular in rural Ontario.” Indeed, despite the artistic success of 2013’s tour of The Odyssey (adapted from Homer by Canadian playwright Rick Chafe), it is interesting that audiences declined when they saw Shakespeare was not offered. For many of these communities, Driftwood is Shakespeare, and vice-versa. The company’s ability to bring out Shakespeare’s comedy, passion, and excitement in their own backyard has grown a Shakespearean culture with accessibility at its very heart. In many communities, the Driftwood performance is a one-night-only affair, an event not to be missed, and one stridently supported through catastrophes of weather, technical failure, or bug infestation. As company member Brad Lepp attests, it is elements like this which make the company “[feel] like you and the audience are on the same team.”

Then, of course, comes the monotonously regular question of why audience numbers in Toronto do not match those on the road. This is simply addressed in some senses – there’s more going on in Toronto so audiences are more discerning; the company is transient so people forget when we’re in town; there’s too much Shakespeare in Toronto (!) – but it’s impossible to shy away from the fact that regardless of these factors, audiences in city and rural communities get the same show, but react differently. Jeremy nicely summed up this phenomenon by noting body language: a rural audience will start watching the play sitting forward in their seats, excited the event has begun, and will settle back once they become comfortable. Toronto audiences are the inverse: they begin the performance sitting back – “here we are now, entertain us” – and lean forward if they are impressed with what they see. Interestingly, both sets of patrons usually end the play with very similar posture, which we might fancifully attribute to the transformative power of theatre but more fittingly speaks to the detailed care that makes up a Driftwood show, regardless of who its audiences are.

The places that Driftwood tours is often a topic of conversation, which turns to questions about why the company has not struck out for the more lucrative opportunities touring in the US, or across Canada. Jeremy is firm that Driftwood is a strictly Ontarian company. Ontario has been good to Driftwood, and Driftwood has tried to return the favour in communities as small as 700 citizens (Westport, ON) even though it’s tough to cover costs with the Pay-What-You-Can take. An important element in the Driftwood mantra is dedication to communities with an interest in theatre but no local company or means to travel often to Toronto. By offering loyalty, Driftwood receives loyalty in turn, and in many communities audience members approach actors to confide they have literally grown up watching Driftwood shows. This continuity and interest undermines any sense that rural audiences won’t ‘get it’: indeed, some of the most warm and memorable touring moments are often in isolated areas. As Board President Sue McLeod describes it, “I believe the result of [Driftwood’s] accomplishment is that Ontarian audiences are enamoured with William Shakespeare and look to us to continue their annual experience with the arts, theatre, music, and movement.” Time will tell as to whether this translates into the emergence of artists from those communities, but it’s a good place to start.

Driftwood and Innovation

As a composer and singer, Driftwood for me for the last 12 years has been an incredible blessing. It has opened the door to a whole new community of artists with whom I otherwise wouldn’t have had the opportunity to collaborate.

Tom Lillington (Composer and Musical Director, As You Like It, (2002), Love’s Labours Lost (2003), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (2004), Trafalgar 24 (2005), A Winter’s Tale (2006), Much Ado About Nothing (2007), Romeo + Juliet (2008), The Comedy of Errors/King Lear (2009), Twelfth Night (2010), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (2012), The Odyssey (2013), The Tempest (2014), Food of Love (2014))

While Driftwood has primarily made its name as Shakespeare company, we must not forget innovations that characterise the group’s growth. From humble beginnings with a tiny budget dedicated exclusively to equipment rental (and how fitting that Jeremy Smith’s ‘rude mechanicals’ were staging A Midsummer Night’s Dream!), it was only six years before they hired their first Equity actor – Xuan Fraser, as Othello. From there, the professionalism of the company continued to burgeon.

From just its third season, Driftwood experimented with play workshops and smaller scale projects, on scripts by Daniel MacIvor, Morris Panych, and new projects by company members Steven Burley and Chad Hershler. Jeremy Smith refuses to stagnate or rest on Driftwood’s laurels, and is always thinking years ahead about how he might further develop. Nowhere is this better exemplified than in 2002’s decision (remember, only the company’s eighth season) to not just stage As You Like It, but to add a capella, choral music, composed by Tom Lillington, Kevin Fox, and Lanie Treen. While the music deepened and became more integral to productions (arguably culminating in the ambitious 2012 reimagining of 2004’s musical A Midsummer Night’s Dream), it is now almost unimaginable to think of Driftwood without the presence of live music. Driftwood quickly became a company for quadruple threats – not just actors who could sing and dance, but actors who could sing, dance, act, AND speak Shakespeare! – which increased the complexity of the company’s interaction with text. With the contribution of such talented composers – particularly the most-regularly-involved Tom Lillington – Driftwood saw new ways to push text, including the memorable all-choral live interpretation of the King Lear storm. Such has been the development of Driftwood’s musical repertoire that it has led to CD releases and concert performances, including 2014’s Food of Love, led by Lillington. The musical element at Driftwood should not be underestimated: it brings a uniqueness and strength to the plays that is only heightened by the liveness of voices. Bethany Jillard assesses it well when she states that “the a capella music integrated into Driftwood’s storytelling is exciting and unique. I loved the way it lifted moments and also strengthened the company’s sensitivity to each other as a team.”

Furthermore, and as signalled in those early play workshops, development of art outside of Shakespeare’s canon is important to Driftwood. In 2002, Jeremy took advantage of an open house at Whitby’s Trafalgar Castle School – a folly built by Nelson Gilbert Reynolds in 1859, which was for a time Canada’s largest private residence – to envisage new ways of creating work, which began with a 2003 site-specific promenade production of Hamlet and later became the iconic and beloved tradition of staging a 24 hour playwriting contest as the company’s major fundraiser. And as if the process of shutting twenty-four artists inside a heritage-listed building and staging the result was not enough, the more recent innovation of adding a jury to the proceedings with the added incentive of a workshop commission has pushed Driftwood in an entirely new direction. Indeed, from the very first year of the Trafalgar 24 jury’s presence, the project stumbled across a bona-fide hit. Steven Gallagher’s Memorial was staged at Trafalgar 24 as a bittersweet comedy about a dying man planning to attend a pre-emptive funeral, but by the time ten months had passed and the commissioned workshop arrived, Steven had gone through a life-changing experience which made this a far more personal story. The workshop’s success led to a slot in the competitive Toronto Fringe Next Stage Festival, where Jeremy Smith’s production was met with universal acclaim, and several invitations for further development in both the United States and Western Canada. The fact that a new play could be so successfully developed from within the auspices of what is generally seen as a Shakespeare company shows just how far things have grown. Two more play workshops (Kevin John McDonald, 2013; Brad Lepp 2014) have been completed, with no plans to walk away from this new developmental arm. Indeed, Julia Lederer, the winner of the 2014 jury prize, will have her Trafalgar script, Man in the Portrait, workshopped in early 2015. Most Shakespeare companies restrict themselves to classically-themed or mandated projects, but as Jeremy so often states, his interest is in human beings, not just a narrow set of projects by one writer. True, Shakespeare wrote humanity better than just about anyone, which explains Jeremy’s passion, but his interest in the human experience means that Driftwood and innovation go hand-in-hand. After the many twists of the past years – the reading of William Shakespeare’s Star Wars and the 15th anniversary A Man for All Seasons nude calendar (featuring twelve of the bravest ‘Men of Driftwood’ posing as Shakespearean figures sans couture) come to mind – it’s a fair bet that there are some interesting ideas ahead.

Peter van Gestel, Shannon Currie, Sabryn Rock, Helen King, Steven Burley and Peter Nicol in ‘The Comedy of Errors’ (2009)

The Driftwood Family

“I’ve been in the industry for over 10 years and there has never been another theatre company that feels more like home to me than Driftwood. To put it simply – Driftwood is family to me.”

Stephanie Nakamura (Stage Manager, Trafalgar 24 (2006), Much Ado About Nothing (2007), Romeo + Juliet (2008), The Comedy of Errors/King Lear (2009); Apprentice Stage Manager A Midsummer Night’s Dream (2004), The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged) (2005-06))

“Even since I’ve known the Driftwood crowd, which has only really been a few years, I’ve watched us go from what felt like a bunch of kids to adults with spouses and families. There’s a distinct second generation now.”

Michelle Bailey (Costume Designer, Twelfth Night (2010), Macbeth (2011), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (2012))

Today, wherever I go, I still reference that experience, and nearly everyone knows about Driftwood and has a deep respect for the company and what it accomplishes. What’s more, I continue to run into alumni… “Woodies”, at every stage of my career, and that always gives me a warm feeling to know that we never really leave, we just circle back every so often.

Brad Lepp (Playwright, Trafalgar 24, 2004-07, 2009-10, 2013, Beyond the Castle: The Long Game (2014); Director of Production & Assistant General Manager, (2002-06))

As I compiled this abbreviated history, I felt it particularly appropriate that Driftwood’s 20th Anniversary Season was subtitled ‘We Are Family.’ Not just a marketing slogan to shill the 2014 production of The Tempest, ‘family’ is at the very core of what the company stands for. I reached out to past artists, board members, and audiences personally and through social media, and was gratified with how many responses mentioned the idea of a Driftwood ‘family’. Company members have met, fallen in love, and married on Driftwood shows. Some have literally grown up with the company, sticking with the group from high school into their late thirties (so far). Lifelong friendships have been forged. Artistic careers have flourished in a safe space, and then have had the chance to be redirected, from onstage to offstage roles. Truly, Driftwood is more than just the sum of its productions.

The actors who have made up the performing face of the company over the last twenty years are an impressive bunch. The 1995 A Midsummer Night’s Dream featured high schoolers, university students, friends of friends, and other amateur lovers of Shakespeare, all working for free. Little could they imagine that twenty years later, the professional version of Driftwood would have attracted so many impressively credentialed performers, and that it would launch the fledgling careers of so many rising stars. From its outset, Driftwood compiled a set of ‘regulars’ who you might reliably expect to see on a Driftwood stage. Jeremy began the company as an actor, and appeared in a handful of early shows before taking over as dedicated director; Steven Burley, officially now the company’s ‘artistic partner’, has appeared in more Driftwood shows than anyone else, from the original Oberon (a role he didn’t actually audition for, but stepped in after an actor, whose name long ago disappeared into the mists of memory, pulled out weeks before rehearsal started), and to this day, both onstage and off (Steven likely has sold you a can of Dr. Pepper at the concession stand over these years). Dan Gallo, the original 1995 Robin Starveling rose to become the company’s go-to technical brain (by way of playing Macbeth in 1998), and met his wife, costume mistress Michelle Bailey, on Driftwood’s Twelfth Night in 2010: their daughter, Evelyn, is nearly one. Peter Nicol, who traces his membership back to 1999’s Twelfth Night, is another familiar face who was to return in 2014 for the anniversary remount of The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged) before a last-minute relocation home to Edmonton. Cathy Bate, the company’s 1995 Nick Bottom, is now a successful lawyer, past Driftwood president, and fixture in front-of-house; Brad Lepp, Smith’s fellow Queen’s alumnus, has acted as Driftwood director of production/assistant general manager and has written almost annually for the Trafalgar 24 project, winning the development award in 2013. Other gigging artists-turned-fixtures include talents like Helen King, Peter van Gestel, Madeleine Donohue, Tim Machin, Susan Green, and Chris Kelk, all of whom exemplify the bond that Driftwood offers on tour.

Importantly, Driftwood has become a place where young actors – often fresh out of theatre school, sometimes even still at high school – may hope to get an opportunity to work on their first tour. Bethany Jillard, who has starred for the past four years at Stratford, playing roles like Lady Anne (Richard III), Desdemona (Othello), and Hermia (A Midsummer Night’s Dream) credits Driftwood with giving her career a start: “Driftwood is the company that took a chance on me!… while I was still in school, when I had no experience. I learned invaluable lessons about what it took to create theatre professionally, I gained confidence and grew as an artist every season.” Similarly, the Juliet from 1996’s Bard’s Bus tour of Romeo and Juliet was a teenaged Sarah Wilson, who returned to Driftwood for three more seasons before she joined Soulpepper’s acting academy and went on to star on many of Toronto’s biggest stages. Ben Mehl, a young actor with such promise in three Driftwood productions (including his 2004 portrayal of Romeo), has found terrific success in the United States after time at the prestigious Tisch School for the Performing Arts at NYU. Director Alan Dilworth and actor Maev Beaty, both now making waves on a national scale, appeared as young actors in Driftwood productions, including Dilworth’s interpretation of Hamlet at Trafalgar Castle. Peter van Gestel, mentioned above as a Driftwood regular, had a successful career at Stratford in the midst of his many appearances on Driftwood stages, before achieving his Master’s degree in theatre education and heading up Driftwood’s ‘Creative Roots’ youth training programme. Other wonderful performers moved seamlessly from the Bard’s Bus to the Tanya Moiseiwitsch stage at Stratford, including Daniel Briere, Karl Ang and Sabryn Rock, while the latest generation of Driftwood youth, like Mark Crawford, Nathan Carroll, Justin Goodhand, and Alexis Gordon, go from strength to strength in their early careers, with nowhere to go but up.

While the development of young actors has been one of the most gratifying elements to Driftwood’s achievement of the last two decades, the ability to attract established and senior artists has ultimately strengthened and validated everything that the company has built. Steven Gallagher, a sublimely talented comic actor and playwright, auditioned (quite by surprise!) for 2009’s King Lear/Comedy of Errors and stated that he was happy to tour on a shoestring for a summer because he felt it was his duty as an older actor to repay the lessons he had been taught by senior actors as a rookie in New York twenty years prior – although he’s confided that he was never fond of the then-rudimentary Bard’s Bus! Paul Dunn, another hugely respected artist, joined the tour in 2012 with an opportunity to play Puck – a role he had always wished to play – and brought the weight of his experience mingled with a terrific sense of generosity that elevated the production immeasurably. Dunn notes that ‘…the inventive spirit of the company encouraged me to be inventive, and the result was a performance that surprised even me, and remains very dear to my heart.” Richard Alan Campbell brought his experience to a devastating interpretation of the Duke of Gloucester in 2009’s King Lear, and brings gravitas and texture to a memorable interpretation of Prospero for 2014’s The Tempest. RH Thomson, Xuan Fraser, Michael Shamata, Chris Stanton, Richard Lee, Daryl Cloran, Sue Miner, Oliver Dennis, Joseph Ziegler, Michael Hanrahan, and Geoffrey Pounsett are just a few more of the respected, established artists who have appeared with Driftwood in a variety of roles, validating the company’s rise and offering an invaluable set of experiences for young actors to learn from.

Beyond Twenty

My favourite show is the ‘next’ show, whatever it may be. Part of my love of Driftwood is its unstoppable ability to ask more of itself every time it works, whether that is a new Canadian play, a Greek Tragedy or William Shakespeare (Complete Works or Star Wars). I am constantly amazed at the endless well of skill, creativity and passion that DTG continues to produce. And I stand back, in wondered awe, at watching the folks and their craft at its best.

Sue McLeod (Board President, 2010-present)

The future for the Driftwood Theatre Group is bright. The successes over the past twenty years, extended far beyond simply staging Shakespeare in an outdoor setting, have meant that the company is more than just the sum of its parts. Jeremy Smith remains the face of and the drive behind Driftwood, but he is under no illusions that the company could not exist without him. Driftwood has become a force in itself – one that would, no doubt, be something different with someone other than Jeremy at the helm – and such a force is worthy of respect for carving its place in the brutally competitive Canadian theatre scene.

The way we produce and process theatre has changed since 1995: the internet was is in its infancy then, but dominates everything now. Marketing has changed, economics have changed, audiences have changed. Given the economic realities over recent years, the difficulty in gaining funding, the proliferation of work on a saturated market, and the influence of a new, internet-savvy consuming public, Driftwood probably shouldn’t still exist. Many other artistic directors might have (and indeed have) thrown in the towel by now, or reduced their ambition to make up for the external restrictions. Not only has Driftwood prevailed, but it has grown and flourished, taking on new challenges and new ideas – some hugely successful, like Trafalgar 24; some less so, like the short-lived Shakespearience Festival – to extend the stamp of the group.

Jeremy Smith has no interest in establishing a permanent home for the company, or to somehow find stability. The chaos of the Bard’s Bus tour is what this company was founded on, and it’s what keeps it alive. It has been a twenty year education for Jeremy (“my version of grad school”, he says), one in which he has taken the opportunities to learn and re-evaluate, to fill gaps in his understanding on how to communicate with an audience. Crucially, of course, the rise of Driftwood has been more than a one-man show. The company will continue to grow and thrive as long as exist those passionate ‘wits’ and their love for this ‘drift.’

Works Cited

Heatley, Stephen. “Adapting Shakespeare to an Outdoor Prairie Reality: Is Shakespeare a Prairie Playwright?” Canadian Theatre Review 13 (Summer 2002), 63-66.

My heartfelt thanks to everyone who offered their time and words to help build this piece both by email and through social media. I was unable to use all of your contributions, but they have been appreciated.